Takuan’s Journey to the West

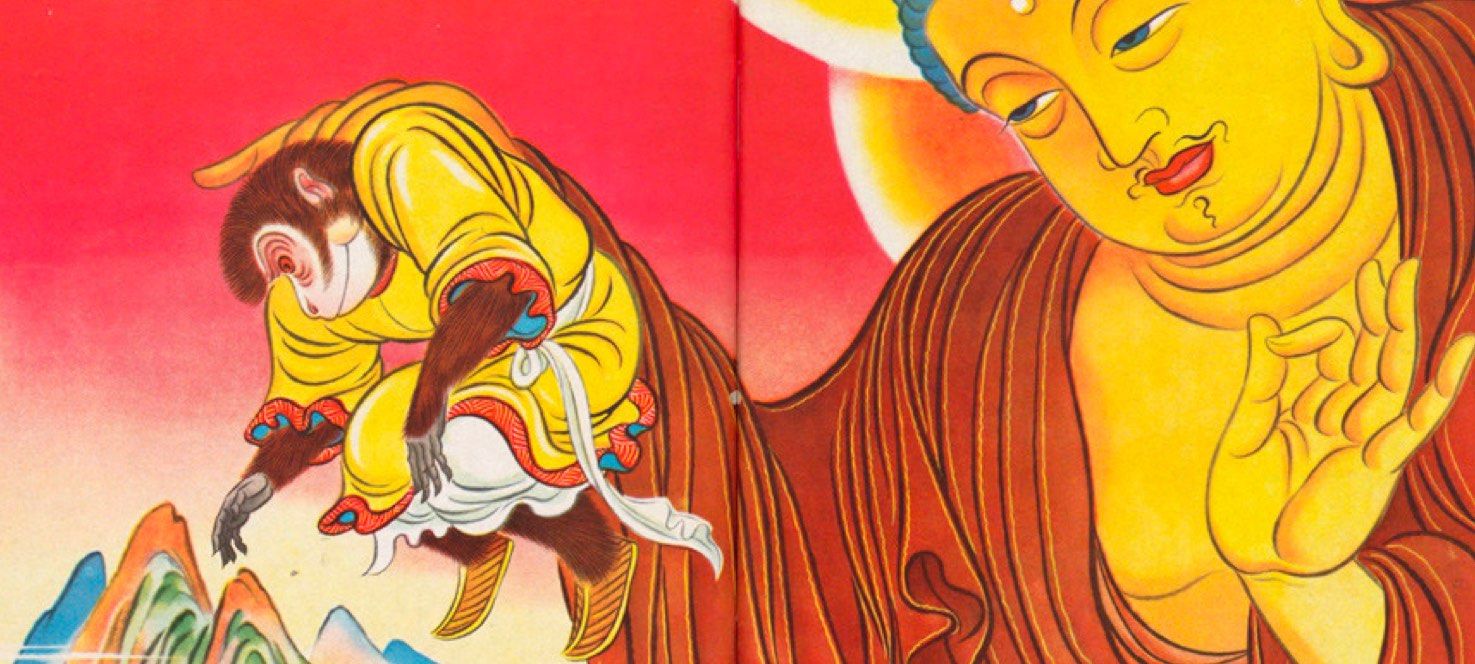

Recently, we released the second volume of ‘Takuan’s Adventures,’ which goes by the title ‘Hunters of Weredemons.’ In the book, it becomes apparent that ‘The Adventures’ have lots in common with one of the four classic Chinese novels. ‘Journey to the West’ is the title of that novel, and to the modern reader, it’s known as ‘Son Wukong, the Monkey King’ or simply ‘Monkey.’

The similarities (and differences) between ‘Takuan’s Adventures’ and ‘Journey to the West’ are no coincidence, and I’ll tell you why.

When I was working on the sci-fi novel series ‘Demons Within,’ its world needed a story. A history even. This often happens with fictional worlds: just having a set of random facts isn’t enough, not only for the author and readers but also for the characters themselves.

Every thinking person, sooner or later, thinks about the past: about their own as well as about the days gone by. What will my heroes look back on? Where will they get knowledge about the past of their world?

Historical Novel, History Textbook, or a Fairy Tale?

I didn’t want to write historical treatises and dictionary encyclopedias. Reading those isn’t the most exciting thing to do either. Especially for the younger heroes of ‘Demons Within.’ So, I decided to give the story a more entertaining form.

The dominant culture of the ‘Demons’ world arose from a fusion of Asian traditions: Indian, Chinese, and Japanese. In their past, these traditions faced the same challenge that I did – to preserve the history of the world, they needed a medium that could be easily and happily passed down through the ages. This medium is an epic novel.

Indian ‘Ramayana’ and ‘Mahabharata’; Japanese ‘Kojiki’ and ‘Kujiki,’ ‘Nihongi’ and ‘Kaidans’; Chinese classic novels ‘Journey to the West,’ ‘Romance of Three Kingdoms,’ ‘Water Margin,’ and ‘Dream of the Red Chamber’ — here are perhaps the most famous of them. There’s plenty to choose from!

I chose with no hesitation: most of all, stories I love to read (and write!) about tricksters, cunning and foolish at the same time. Sun Wukong from ‘Journey to the West’ is just that: he fools both gods and demons, but he falls for their tricks as well. ‘Journey’ takes place both in the mortal world and in the Heavens, and by following this canon, I’ll have enough space for all the necessary details for the world building.

Specifics of Translating Epics and Fairy Tales

‘Journey to the West’ was published at the end of the sixteenth century without an author’s name. Since then, it has been translated into all the languages of the world, each time adapted to the local style of mythology and folklore.

The work done by the translators of ‘Journey’ helped me both in writing and translating ‘Takuan’s Adventures.’ In each case, I (and my team of translators) followed the same path: first, re-read the corresponding translation of ‘Journey’ (or even more than one!) from cover to cover, then highlight stylistic devices (both adaptations of the original ones and translation-specific), and only then adapt the text.

For example, in the English translation of ‘Takuan’s Adventures,’ each chapter has a couple of aphorisms as a title: ‘Even Heavenly Luck Cannot Root Out Human Vices,’ ‘Tricks of Today Become Sorrows of Tomorrow,’ ‘Where Stars Predict Misfortune, the Good Merchant Sees Only Opportunities.’

In other languages, the translation follows different tradition. As the title of each chapter, it gives a summary: ‘Chapter Two, which talks about how Ta-Guan got to the Heavens and caused a commotion there,’ ‘Chapter Eight, which talks about what happened at the inn, and how the sorcerer Bricabrac was mistaken for a demon hunter.’

Following the Style of Classical Chinese Fairy Tales

Despite their individual differences, all translations of ‘Journey to the West’ (and, therefore, of ‘Takuan’s Adventures’) are united by a style and structure, which is evident to the reader.

Both are presented in the form of a fairy tale. The purpose of this style is to give the reader the impression of the ‘reality’ of the story being told. The reader, much like the characters in my other novels, will read a book that was written many centuries ago. The book tells the story as if written down from the words of a narrator who lived in the times the book is describing. The storyteller knows a lot about the heroes, about past events, and even about those that will happen.

The style of the stories helps the reader to look at the world from a somewhat archaic and even magical perspective. This perspective allows the author (myself) to move away from an overly realistic presentation of events and instead use tropes from a world filled with magic, demons, and wandering years.

‘Adventures’ takes place in the darkest period of the world—just after the Great Storm—when humanity returned from technology-rooted rationality to a mythological and magical way of looking at the world.

Borrowed Plot and Weredemons in the Details

In the first book of ‘Adventures,’ we get acquainted with the stone marten Ta-Guan. The reader who remembers ‘Journey to the West’ well can’t help but associate the stone marten with the monkey, which, just like said marten, was born from the stone rock. Only instead of a sunny mountain of fruits and flowers, the marten is met by the cold airs of Auyasku. Like the monkey, the marten wants to become the leader of her tribe, climbs up to the Heavens, and makes a commotion there.

The reader, who has caught this resemblance by the tail, will wait attentively for the marten’s liberation. Their expectation will be rewarded in the second book. There are even more similarities with ‘Journey to the West.’ There is a monk who received a divine quest, a sturdy wandering warrior, and a golden monkey tail. But there are also differences. A special meaning is hidden in them, accessible only to those who are well-acquainted with the source.

With the third book, the story of ‘Adventures’ flips over the spine of ‘Journey’ and sets it on its own voyage toward events that will determine the future of the world. The very future that awaits the reader in the novel ‘Demons Within.’

Using Style to Convey Story Mood

‘Journey to the West’ is a fantastic satire, the style of which moves from pompous epic to everyday banter and back. Its characters combine nobleness and ignorance, cunning and stupidity.

This is a comedy adventure story. The characters in this story are very emotional; they vividly express these emotions. They jump up, scream, yell, clap, roll on the ground, point fingers, and do other things that we don’t normally expect from adults.

This is a bright and colorful story that, at the same time, doesn’t burden itself with many details. It’s like an animated film in which the continuous action keeps the viewer focused on themselves, preventing them from leaning back in their chair and thinking.

Despite all the joking and banter, the story carries deep philosophical and religious meanings and acquaints the reader with timeless moral and ethical values.

The reader will find all this in ‘Takuan’s Adventures’ as well. All this and a little more.

Stylist’s Toolbox

One of the stylistic tools—the naming of chapters—is described above. While writing and then translating, I collated a whole memo titled ‘Stylist’s Toolbox,’ excerpts from which I’m sharing here.

Structure of a Chapter

Another tool is the structure of a single chapter: each chapter begins with the word ‘So,’ followed by a short one-paragraph description of the events of the previous chapter.

Then new events are outlined, and the chapter always ends in the same way. The last sentence has a special structure and a special purpose – it encourages the reader (sometimes very insistently and directly) to continue reading if they want to get answers to the questions that come to their mind.In case no questions come to the reader’s mind, some are offered in this sentence.

The format is very simple: the sentence begins with ‘If you want to know’ followed by a couple of questions and ends with a request-order ‘listen to the explanation in the next chapter.’ For example, ‘If you want to know what happened on Takuan’s journey, you must listen to the explanation in the next chapter.’

Point of View

Working with the point of view (POV) is another tool for a stylist.

The fairy-tale style requires some detachment, so the narration is always conducted in the third person. The narrator, of course, can ‘glimpse’ into the character’s mind, but the narrator (and the reader) always look at the thoughts of our hero somewhat from the sidebar.

The style uses this technique to make room for humor and irony.

Instead of ‘joining’ a character heading for trouble and experiencing that trouble with them, the reader sits next to the narrator, and together they watch the characters who get into trouble, struggle helplessly through the trouble, don’t give up, and in the end, against all odds, the characters win.

With the help of this technique, the tragedy of situations becomes comedy.

Clichés and Special Words

Another tool is the special words and clichés, of which there are plenty in the source. Here are some observations and examples.

- Fights are often described as ‘beautiful’ and ‘long,’ and in such a description, details are omitted. Instead, it says this: ‘A fight broke out between them. Opponents clashed thirty times, but so far it was not known who would win’ or ‘An angry banter began between the opponents, after which they entered into battle.’

- Characters often rejoice with delight (and generally get excited about other feelings as well). For example, ‘he came into such confusion that he even changed in his soul’ and ‘Out of anger, he began to pull his ears, rub his cheeks furiously and bounce.’

- Dialogues are often accompanied by specific archaic remarks such as ‘said such words,’ ‘addressed with such words,’ ‘answered the greeting and said,’ ‘shouted,’ and even ‘yelled.’

- Characters often kowtow and act with exaggerated respect.

- Explanations, diversions, and topic changes are introduced explicitly. For example, ‘this is what was written there,’ ‘And what would you think it turned out to be?’

- The clothes of the characters, landscapes, and food (feasts and various types of dishes) are often described in detail.

Fruits of All This Labour

In each of the translations of ‘Takuan’s Adventures,’ the readers easily recognise Asian mythology, notice the poetic style and ornamental descriptions, and enjoy the unusual metaphors.

All these techniques invite the readers to take a break from the modern daily bustle and plunge into the magical world of the book, where the celestials argue with each other, demons arrange intrigues, and mortals surrender to the power of their passions.

‘The most fascinating element about this book for me is the style of writing. The writer has a smooth and unique style. It’s artistic but not complicated. It’s a special book away from modern life and its hustle. It has this ancient eastern theme and takes you to a very different place.’

— Hager Salem, Online Book Club